Memorising Scripture with Anki

You can eat your cake and keep it too

My son was born in 2022. Other than that great joy, probably the single biggest (and very positive) change in my life last year was that I started using Anki to memorise Scripture.

This post comes in three parts. The first is a brief pitch for Scripture memorisation. The second is the pitch on Anki: I’ve found that memorising Scripture with this app easily beats out all other ways I’ve tried, and I'd like to get you as excited as I am about the possibilities. (Other, similar apps are available. I’m going to describe the one I know.) The third is the nuts and bolts: how to download, set up and start using the program to learn Scripture. Some readers will want to skip one or more sections; whatever you read, I hope you find it useful.

Scripture Memory

I am by no means an expert in Scripture memory. I certainly haven't got much Scripture in my head yet. But already, after a stop-start year of working at it, I'm hooked. There's something about memorising Scripture that's different from just reading it. The great anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce apparently memorised Psalm 119 and used to recite it while walking to and from Parliament. One day, during a particularly brutal period, he wrote in his journal, "Walked from Hyde Park Corner repeating the 119th Psalm in great comfort." Great comfort. I haven't memorised that monster of a psalm, but from learning much smaller bits of Scripture I think I know something of his experience. Knowing Scripture by heart means that it's with you. It's in you. And it can be remarkably comforting.

It's not only comfort (though which of us wouldn't like more comfort?). In that same psalm, the psalmist says, I have stored up your word in my heart, that I might not sin against you. (Ps 119:11). Storing up Scripture helps enormously with holiness. If you know the words of Scripture, you can call on them for prayer or wisdom or strength, wherever you are. They’ll be with you as you read other parts of Scripture, shaping the way you read and throwing up connections you’d never otherwise have seen. And, if the words are there in your head, they might even ambush you, popping up when you least expect them, convicting you or guiding you. Memorising Scripture puts a sword in your hands; and it hands the Holy Spirit a scalpel, with the sober words, “use this on me whenever you like.”

And not only is Scripture memory good once the memorisation is done; the process of memorising is deeply healthy too. When you read a verse, it’s so easy just to move on. But when you learn a verse, you have to sit with it. You have to consider every word. Little surprises in the text become more obvious; you repeat the verse to yourself wrong, and you got it wrong because your version seemed more natural to you, and then you wonder, so why did the Holy Spirit actually write that? You have to wrestle it; and, if the Lord blesses you, you win when it masters you.1

Memorising Scripture used to be more common. At the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, for example, it was decreed that you couldn’t be made a bishop if you hadn’t memorised all the psalms (Canon 2). If you read older writers like Augustine or Athanasius, one of the most striking things about them is how, without the help of any concordances or Bible software, they could pull together so much Scripture in their arguments. They had stored it away in their hearts. Today, we have all the tools – the software, the concordances, and so on. Bibles on our phones. Perhaps this is part of the reason we memorise so little: why learn it when you can just look it up? But there is a big difference between having a Bible available to you and having Scripture in you.

Tech doesn’t have to take memorisation away from us. In fact, it can help. (Tech is meant to help, after all. You didn’t buy your phone because you wanted to distract yourself and be less productive.) My experience is that it not only can help, but that it has helped.

Spaced Repetition Software

The great difficulty is memorising is not learning the material; it’s keeping it. Not acquisition, but retention.

Many of us know this from our schooldays. You face some exam, and you need to know a bunch of things: history dates, language vocab, details of the digestive system. So you learn it, you sit the exam, and a day later it’s gone. Learning the material wasn’t too hard, but you don’t keep it. I sat an English exam once where I was able to talk intelligently about Shakespeare's The Tempest for a whole essay. Today I couldn’t accurately describe a single scene. I think Caliban sniffs a sleeping girl at one stage (Miranda?)!? Not sure. At some point the same girl watches a guy get off a boat, and at another point her dad holds a book while looking at a storm. But that's about all I've got! I learned lots and lots, but it's gone now.

There are two key ways to improve your memory retention. The first is to learn the material more thoroughly to start with. This is the basic idea behind the “memory palace” approach made famous by the BBC Sherlock Holmes, but you don’t have to go as far as that to get the benefits. An isolated fact, poorly understood, will be gone from your mind very soon; but a bit of material connected to others by a thousand threads will hold for a long time. The more you think about what you’re learning, and particularly the more you connect it up with other things in your mind, the longer you’ll keep it. With Scripture memory, if you read the verse (visual), say the verse (audio/kinetic), write the verse out (kinetic), go through the verse emphasising a different word each time, etc, this all helps. Some people write out the first letter of each word in a string. Or you might try and draw a little sequence of pictures. Whatever works for you! I don’t go in for the complicated stuff, tending to stick to the “read the verse and then repeat it a few times” school of memorisation, but it’s certainly true that the more thoroughly you learn something to start with, the longer you’ll keep it.

However, that first principle pales in comparison with the second, which is review. You have to return to memories to reinforce them. This is not just true of the part where you’re “learning”. It’s always true. There aren’t two phases of memorisation, the “learning” phase where you have to review and the “learned” phase where it just sits there. However well you’ve learned it: on a long enough timeframe, if you don’t return to it, it goes.2

For example, when I was a kid, my parents got me to learn a few poems. One was Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky; another was John Masefield’s Sea-Fever. I liked both very much, and I learned them well. But today, I could recite Jabberwocky without any trouble, and all but the first two lines of Sea-Fever are gone. Why is that? Review. Sea-Fever is a lovely poem, but since I was about ten I don’t think there’s been an occasion where I’ve wanted to go over the whole thing – the first two lines were enough to conjure the flavour. But Jabberwocky is fun and silly, and I’ve probably repeated it to myself or others maybe ten or fifteen times since I turned ten. That’s not a lot of times over twenty years! But it’s been enough to keep it, while Sea-Fever has gone by the wayside. (I’m sure there were others that I learned which I didn’t repeat at all, not even the first line, and now they’re gone so thoroughly that I’ve forgotten I forgot them.)

This brings me to the Spaced Repetition approach to memorisation. The fundamental principle of this approach is very simple. If you don’t know something well, review it often; the better you know it, the less often you need to review it. That’s it.

If all you’ve got is physical flashcards, turning this insight into an actual system is a bit of a chore. You have to keep track of when you last reviewed things, how well you know them, etc. This is where tech comes in handy. Your phone can keep track of all those things for you! Just stick it all into an algorithm, and it can tell you what to review when. All you have to worry about is the material. These days there are a lot of apps and programs out there which will do this work for you. Some are more whizz-bang, others more basic. Feel free to check out alternatives, but from here on out I’m going to be talking about the one I use: Anki.

(A quick note for Apple users: Anki is a network of a web app, a computer program, and Android and iPhone apps. All of this is free except the iPhone app, which costs you $25. That’s how the developer gets paid for the rest of it. I honestly think that would be $25 well spent, but that’s easy for me to say as an Android user! Like I say, alternatives are available.)

The process of review in Anki is remarkably straightforward. When you open the app, it tells you which cards are up for review. You open the card and see one side (the prompt). You see if you can remember the material. Then you check and see if you got it right, and let Anki know how you did.

If you got it wrong, the card is reset. You’ll see it again tomorrow.

If you got it right but found it hard, the gap will stay basically the same. So if you last saw it a month ago, you’ll see it again in about a month.

If you got it right and found it either “good” or “easy”, the gap will increase.

And that’s pretty much it! Like most open-source software, you can dive into the guts of the thing and fiddle with numerous presets if that's your thing. I’ve done this a bit. But there’s no real need to; just load up your flashcards and start learning.

For me, the key stat is this. If you learn X new cards per day, you can expect to review around 10X cards per day. This is what the developers of Anki claim, and I can confirm it’s true in my experience. I started using Anki for Bible languages. I wanted to learn Hebrew vocab quite intensively (for an exam), so set myself to learn 30 new items a day; towards the end, I was reviewing something like 180-220 cards a day. (Which sounds like a lot, and it was, but it was rarely more than 20 minutes a day: time well spent.) Meanwhile, I set out to relearn my lapsed Greek vocab, and without any exams to prepare for I settled on the much more sedate pace of 2 new words a day. I’ve done that for about a year now, and again I normally have to review something in the region of 10-16 cards each day. (2-3 minutes a day, including the ones I’m learning. Again: time very well spent.)

Let’s put this together with Bible verse memorisation. Suppose you wanted to learn a verse a day. That’s sounds ambitious, but when you crunch the numbers it’s eminently do-able. If you’re learning a verse a day, you might (generously, I think!) budget five minutes for the verse itself. And then you’ll have to review something like ten other verses. Let’s be generous again and say that it’s ten verses exactly, and that each takes you thirty seconds. That’s another five minutes. That makes ten minutes total – and you not only learn a verse a day, but you keep the ones you’ve learned. And these ten minutes (again, a generous estimate!) don’t have to be in one chunk. You can review a couple of verses while you wait for the kettle to boil, or while you sit on the toilet.

To repeat: eminently do-able.

With a regular habit, what might you be able to get in your head and your heart? Let’s start small. Suppose you learn just one verse a week (a good little habit for a Sunday afternoon, perhaps). After two years – congrats, you’ve learned the book of Philippians (104 verses)! Or, if you prefer, you’ve learned the twenty shortest psalms in the psalter (101 verses). At this rate, it would take you another three years to learn Ephesians (155 verses), and just over two years each for James, 1 Peter, and 1 John (108, 105, 105). Ten minutes every Sunday is not a lot of time! But over 11 years, it got you five epistles in your heart. Nice.

Let’s kick it up a notch. Suppose instead of a verse a week you went for one a day, six days a week. (Sunday is now a rest day!) That’s 300 verses a year. You could learn those five epistles I listed above in less than two years. Alternatively, in just over two years, you could learn all the proverbs in the book of Proverbs (659 verses for chapters 10-31). Romans would take less than 18 months (433). In three years, you could get the whole gospel of John (859).

Suppose you learn two verses a day. That’s a chunk – you’re setting aside maybe 15-20 minutes every day, six days a week. Commitment. But not ridiculous. What does it get you? Well, at 600 verses a year, it gets you the whole book of Psalms in less than 4 years (2351). Hello, bishopric! That’s the longest book in the Bible, by the way. At the same rate, the entire New Testament will take you just over 13 more years (7958).

Let’s say you’re ambitious and you’ve got time on your hands. You aim for – and hit! – four verses a day, six days a week. 1200 a year. In a little over 25 years, you’ve got the whole Bible in your head (31,103).

Forget the individual potential for a moment. Wouldn’t it be good for our churches if it was just normal for people to know a handful of psalms, an epistle or two, and a generous helping of standalone verses? If it delighted us, but didn’t surprise us, to have members of the congregation memorise a gospel? If it wasn’t a particularly striking thing for a pastor (whose job is to give the word to the people!) to know the Psalms, and a gospel or two, and most of the epistles? Wouldn’t that be great? I want to live in a church like that.

Now, reality often deflates. And some of you might have observed that all the timeframes I gave above rely on actually keeping the habits you’ve set! Of course, life doesn’t quite work like that. Stuff gets in and upsets things. Your habit derails. One of the most important things for a good habit is that it shouldn’t be too hard to pick up again if you dropped it.

This is an additional reason that I really like Anki. Like I said, last year my son was born. That knocked my Anki habit off for a good while! I didn’t learn any new stuff, or really review much at all, for about a month; and it took me about six months to get properly back on the Scripture memorisation train. Now, if I was learning Scripture without an app and had a six-month break, it would be back to the drawing board. I wouldn’t be able to remember what I knew and what I didn’t, and would just have to go over everything.

Instead, once I’d started learning properly again, I just set myself to working through my Anki backlog. I’d forgotten a fair amount, predictably, and those verses did indeed have to start from scratch. But I remembered more than you might expect, and on those ones I just kept going where I’d left off. After a couple weeks, I’d cleared the backlog, the from-scratch cards were getting to manageable gaps, and my daily review count was low enough that I started learning new material again.

So, yeah, the timings I gave above are probably a bit optimistic. You should probably inflate them by 20%, or 50% if you’re disorganised, or 100% if you’re planning to have a baby every year.3 Still – even those inflated timings look pretty good, don’t they? Do you think in ten years you'd regret the time spent?

Nuts and Bolts

At this point let’s roll up our sleeves. If you’re sold on the vision, you’ll want to get some software. I can’t tell you how to get going on others (though, again, there are plenty of others), but I can give you a run-through on how to get started with Anki. You can, of course, find all the documentation you need (and lots more!) on the website, but just so you have a feel for what you're getting into I’ll do a basic rundown here.

To run Anki, you want three things: a web account, a computer program, and the app. The app is where you do the reviews, the computer program is where you add new cards, and the web account is what connects the two of them. (You can also review on the laptop, and you can technically add new cards on the app – but I find that the way I’ve described is easiest). Although this sounds clunky, it works fine once you’ve got them set up, and none of the three is at all difficult.

First you need the web account. Set that up here: https://ankiweb.net/account/register

Then you'll want to get the computer program. Here you go: https://apps.ankiweb.net/

And the app is on your relevant app store. As I mentioned earlier, the Android version is free, while the Apple version is £25.

Once you’ve installed program and app, you use your web login on both, and hey presto. You’re all set and ready to go. All you need now is some flashcards.

There are two basic ways to get flashcards. You can build your own, or you can just nick someone else’s. There’s a whole part of the Anki website where you can browse other people’s cards that they’ve uploaded: Shared Decks. Currently, there’s not a ton of Bible on there, but there is some.

However, let me make an offer to anyone reading this. If you want to learn Scripture, and you don’t consider yourself tech-savvy enough to put the cards together (as I’ll outline below), just get in touch and I will do my best to make them for you. I may have to pull the plug on this offer if I get deluged (which I’d love!), but seriously. Get in touch.

Still, to get you started, here are two of the most useful ways to make Bible flashcards (in my experience).

1. The Basic Card

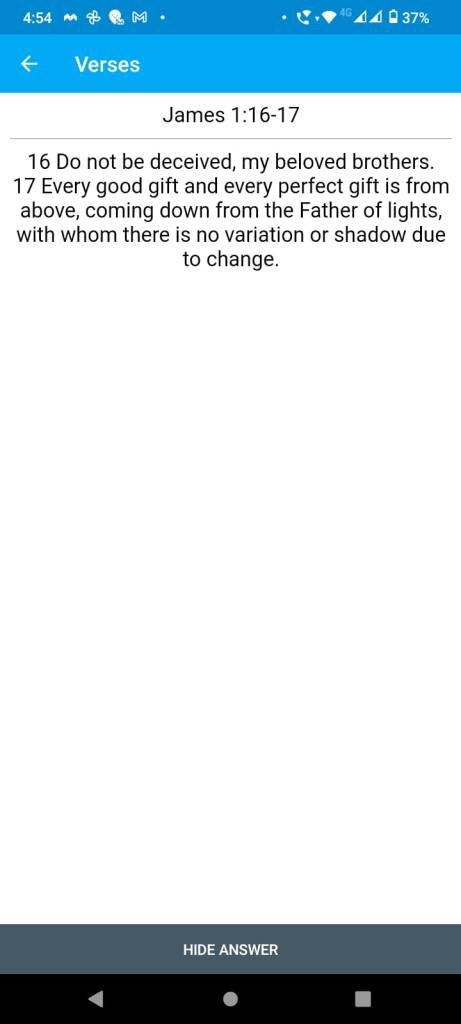

This is just as you’d imagine. On the prompt side of the card, I have the Bible reference. On the other side, I have the verse.

Here’s what the prompt looks like:

And here’s what the reverse looks like:

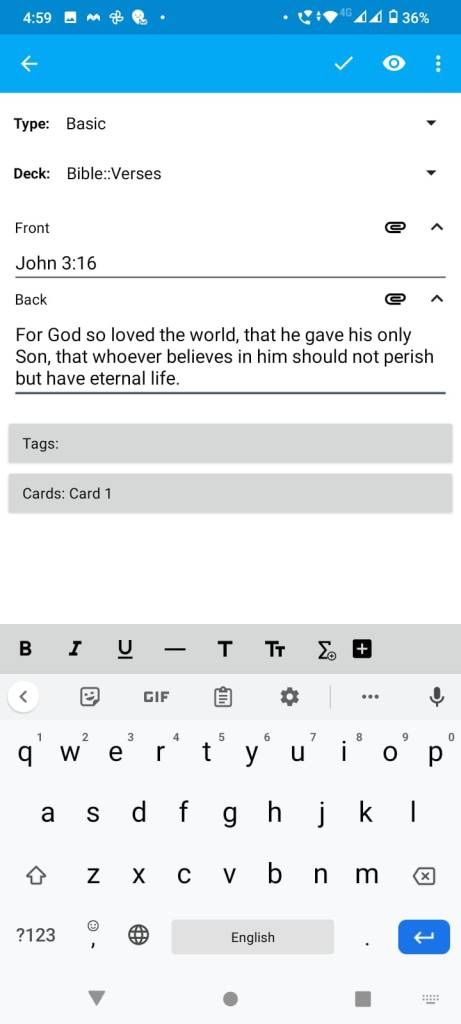

Like I say, really basic. This is simple enough that I can put the card together straight away in the app, like this:

Easy peasy. And if all you want to learn is that particular verse, what more do you need? Off you go. For longer chunks, however, I use the following:

2. The Sequence Card

If you want to learn a chunk of Scripture (say a psalm, or a chapter of a gospel), chances are that you don’t mind too much about knowing each individual verse number. Rather, you’d like to know the whole thing. And the basic requirement there is that (a) you know how the passage starts and (b) given any line in the passage, you know the next line.

In other words, if you tell me you learned Philippians, and I go, “cool, what’s Philippians 3:10”, it’s no problem if you can’t immediately tell me. But if I read you Philippians 3:9, you should be able to carry on and remember 3:10.

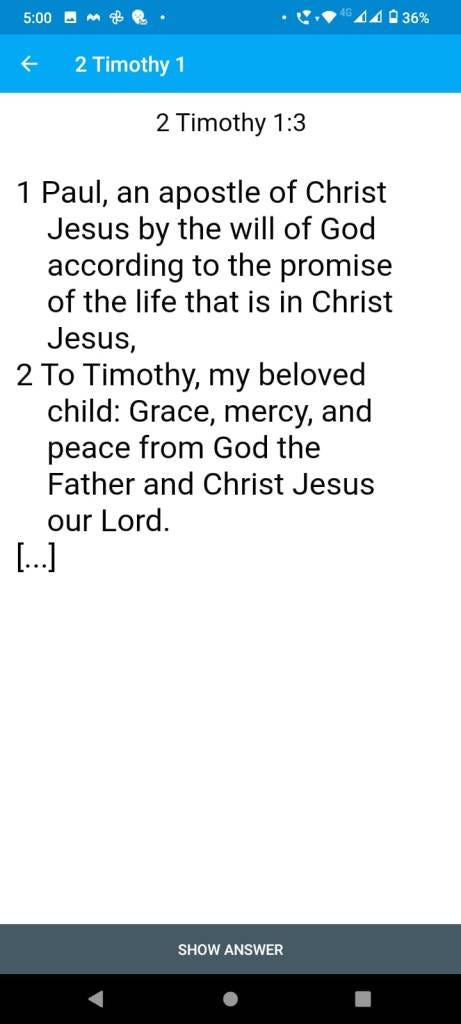

So what I use is the following: one card per verse. But on the prompt side of each card are the previous two verses.

Very helpfully, someone who was interested in learning poetry wrote an add-on for the Anki app which will spit these cards out for you. It’s called the Lyrics/Poetry Cloze Generator (LPCG), and it’s great. With this add-on, if you want to turn a whole chapter of Bible into one-verse flashcards, you just paste the whole chapter into the generator and you get one card per verse. Pretty dreamy! You can get it here, as well as all the documentation you need to figure out how to use it. But to give you a flavour, here’s an example of what the resulting cards look like. The prompt side:

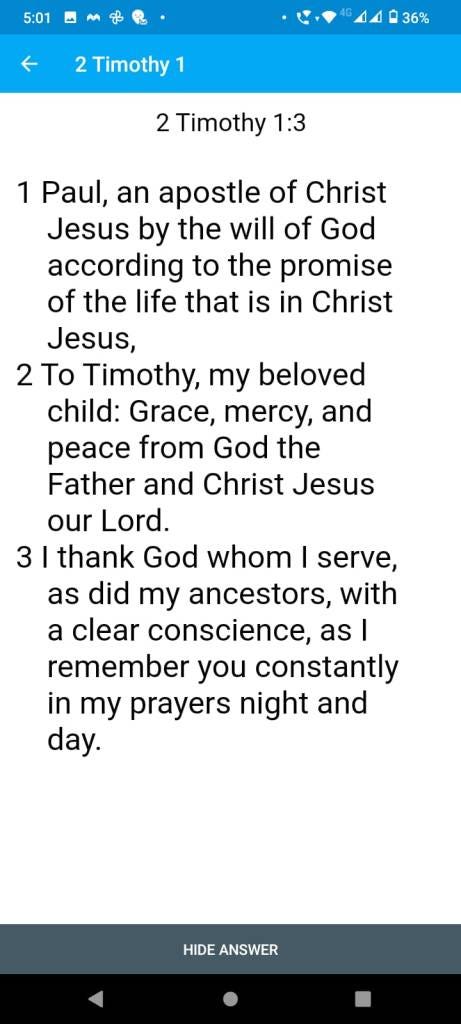

And the answer side:

And there you have it! That's my preferred way of learning blocks of Scripture.

A final reminder: if you would like to get into this, but don't think you can find your way around making the cards, get in touch and I'll do my best to help you. Whether with my help or not, and whether with Anki or not: I hope you get into memorising Scripture, and may God bless you through it.

Like any good thing that isn’t God, memorising Scripture can be misused. We can learn to puff ourselves up with pride; no doubt lots of Pharisees knew lots of Scripture. But, again, that is true of any good thing! The answer is not to avoid memorising, but to seek Christ through it.

In Andrew Davis’s approach to Scripture memorisation - much more hardcore than anything I’m going to suggest! - he ends up saying that at some point, after learning a book of the Bible, you just have to “kiss the book goodbye” if you’re going to keep memorising new stuff. Davis has learned a lot more Scripture than I have, by orders of magnitude, but I’m just not sure he’s right about that.

And, to state the obvious: start small and build up if you find you have space, rather than starting big and flaming out. Better to start on a verse a week and do it than four verses a day and not do it.